Distraction and Make-Believe at the End of the World

- adannoone

- Feb 21, 2025

- 5 min read

The Big Bang. An explosion of unimaginable force, hurtling everything outward at impossible speeds. The universe, born in fire and chaos, has been expanding ever since, galaxies racing away from each other at millions of miles per hour. But this expansion, this relentless outward rush, has a consequence: eventually, everything becomes so far apart that connection, interaction, energy transfer, becomes impossible. The universe cools, fades and dies. What scientists call a "Heat Death" or the "Big Freeze."

We, too, are experiencing a kind of expansion, a social and psychological one. Driven by the allure of instant gratification, the quick dopamine hit, we’re becoming more and more disconnected from each other, even from ourselves. Are we, like the universe, expanding ourselves toward a state of cold, disconnected stillness?

Picture our collective consciousness as an expanding universe, simultaneously growing yet rushing toward its own dissolution. This metaphor captures the essence of our modern predicament: as we reach for increasingly frequent hits of technological dopamine, we accelerate toward a kind of psychological heat death—a state where meaningful energy transfer between human souls becomes impossible.

We find ourselves caught in an unprecedented experiment in human psychology. Our ancient reward systems, carefully crafted over millions of years of evolution to encourage survival and connection, have been short-circuited by what we might call the System—not a shadowy cabal, but rather the natural outcome of market forces colliding with human vulnerability. We've constructed chemical expressways around millions of years of careful neural development, creating shortcuts to satisfaction that bypass the very experiences our brains evolved to reward.

The result is a cruel paradox: we are both oversaturated and starving. Our dopamine receptors, bombarded by social media notifications, endless entertainment, and constant stimulation, become increasingly numb to natural pleasures. Like stars burning too hot and bright, we're consuming our psychological fuel at an unsustainable rate. The more we chase these artificial highs, the more disconnected we become from the very life experiences—deep social bonds, achievement through effort, connection with nature—that our reward systems evolved to encourage.

But there's a deeper layer to this crisis. Humans have always been reality-bending creatures. Long before smartphones and social media, we were masters of cognitive dissonance—creating gods to explain the inexplicable, convincing ourselves that animals don't suffer so we can eat them, building elaborate social hierarchies to give order to chaos. Our current technological addictions are perhaps just the latest manifestation of our ancient tendency to reshape the world in our minds to make it more palatable.

We sit inside our houses and inside our own heads, increasingly unable to turn out the noise of our internal conflicts. Those without homes or digital devices often turn to chemical escapes in the form of drugs and alcohol. But even those surrounded by every modern comfort find themselves in the same ineluctable existence—unable to silence the existential whispers: that existence might be meaningless, that life is fundamentally scary, that none of us really knows what we're doing. The universe just keeps expanding, with or without our understanding.

What makes our current moment unique is not just the intensity of our distractions, but their manufactured nature. The System has effectively weaponized our psychological defense mechanisms, creating what we might call a "manufactured dissociation" from lived experience. The more we use these escape mechanisms, the less equipped we become to handle unmediated and unmedicated reality. Raw experience becomes increasingly intolerable, driving us further into artificial stimulation.

This creates a self-reinforcing loop: our attempts to escape loneliness through digital platforms actually deepen our isolation. The forms of connection offered by social media and other digital platforms are hollow simulations, yet they're engineered to feel more compelling than real relationships, which are messier and require more vulnerability. We're like people who've eaten only processed foods trying to appreciate the subtle flavors of whole ingredients—our ability to engage with unfiltered reality has been damaged by constant stimulation.

So where does this leave us? Unlike traditional addictions, total abstinence from technology is no longer feasible in modern society. Perhaps the goal isn't to achieve some pure, unadulterated connection with reality—that may be impossible given our human tendency to distort. Instead, we might aim to become more aware of our own distortions, to recognize the ways we shield ourselves from uncomfortable truths, and to cultivate a greater capacity for acceptance.

This means accepting the inherent ambiguity of life, the suffering that's inseparable from it, our own limitations and imperfections. It means finding meaning not in some external system of belief or technological escape, but in the act of living itself—in the connections we forge, in the moments of joy and beauty that we allow ourselves to experience fully, without mediation or distraction.

The path forward might involve creating intentional spaces for unmediated experience: digital detoxes, mindfulness practices, face-to-face interactions, time in nature, creative pursuits. But more fundamentally, it requires developing a new relationship with technology and with ourselves. We need to learn to hold both the darkness and the light within us without succumbing to either, to engage with reality more honestly and compassionately, even as we acknowledge our perpetual tendency to distort it.

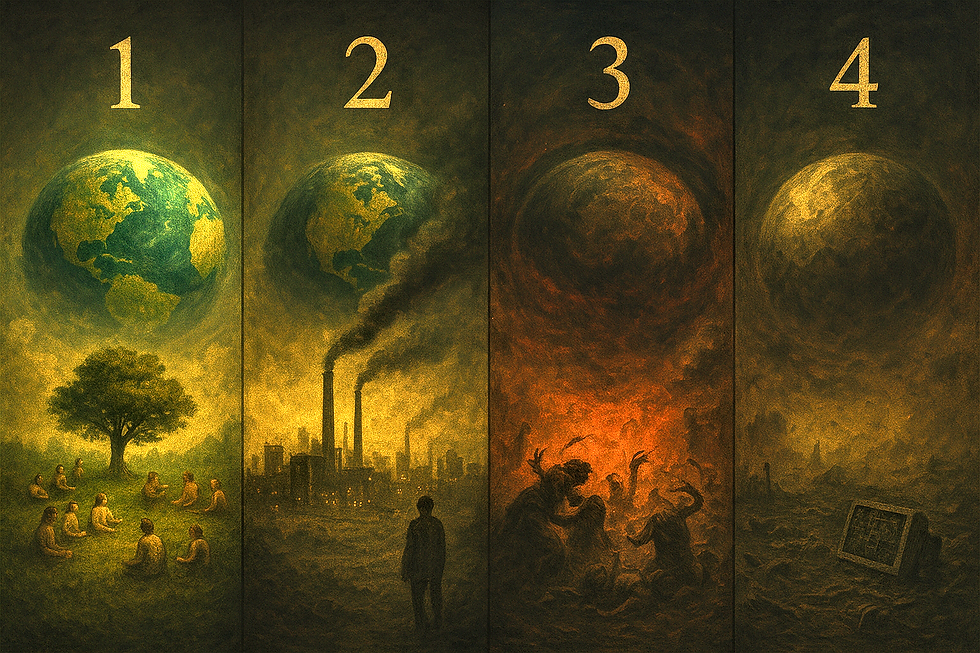

This collective inability to sit with uncertainty and discomfort has profound implications for our response to planetary crisis. As we enter Planetary Hospice—where environmental and societal systems show increasing signs of accellerated collapse—our reflexive turn toward authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, and simplified narratives becomes more understandable, if no less concerning.

These responses represent a mass flight from complexity and ambiguity. Strong-man leaders and rigid belief systems offer what our dopamine-addled minds crave: simple answers, clear villains, and the comfort of certainty. We've abandoned our affair with mystery, our capacity to hold paradox and uncertainty, at precisely the moment in human history when we most need these qualities.

The irony is devastating: our inability to face reality accelerates its deterioration. We seek escape through consumption, distraction, and denial, which in turn deepens the very crises we're attempting to avoid. Like addicts whose attempts to numb their pain lead to choices that create more suffering, our collective coping mechanisms are hastening our decline.

Yet perhaps there's a kind of dark wisdom in this response. Moving into Planetary Hospice, with the prognosis for our future grave and inescapable, perhaps these escapist behaviors are a natural, even necessary psychological response. Just as individuals facing terminal diagnosis often go through stages of denial before acceptance, perhaps our society needs its own process of coming to terms with our predicament.

The challenge, then, becomes not just maintaining our capacity for genuine connection and sitting with discomfort, but finding ways to face our collective reality without succumbing to either despair or denial. We might need to learn how to hold both our grief for what's being lost and our love for what remains, to maintain our humanity in the face of unprecedented change.

This requires developing what we might call "hospice wisdom" or what I've called the Doomee Perspective—the ability to face death and loss while still finding meaning and moments of joy, to accept what cannot be changed while working to help where we can and preserve what can, to hold space for both mourning and celebration. In doing so, we might create a slightly less "diseased" reality, not by escaping it, but by engaging with it more consciously and authentically, even—or especially—in its twilight.

Comments